The Craniosacral System

Bath of Life

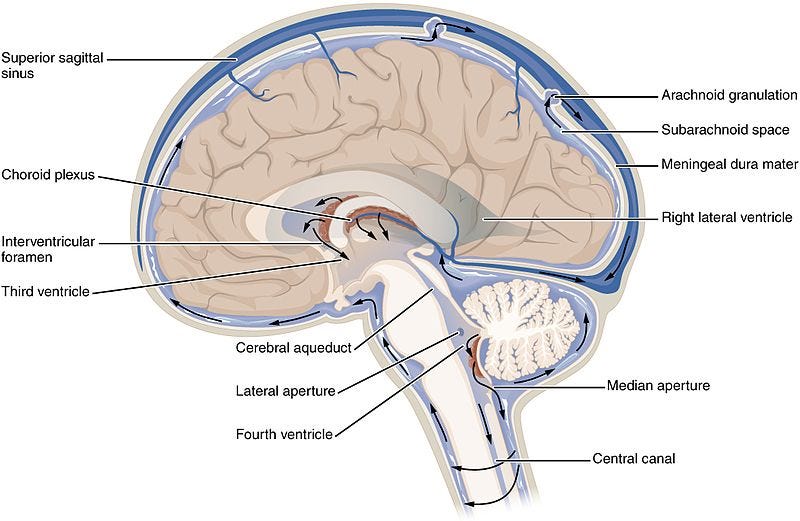

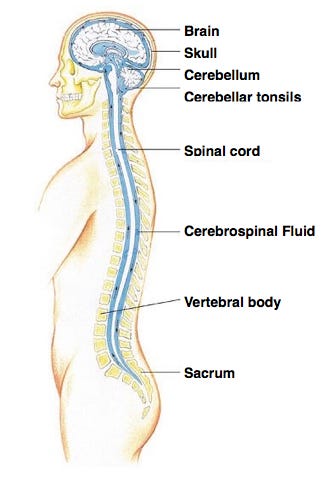

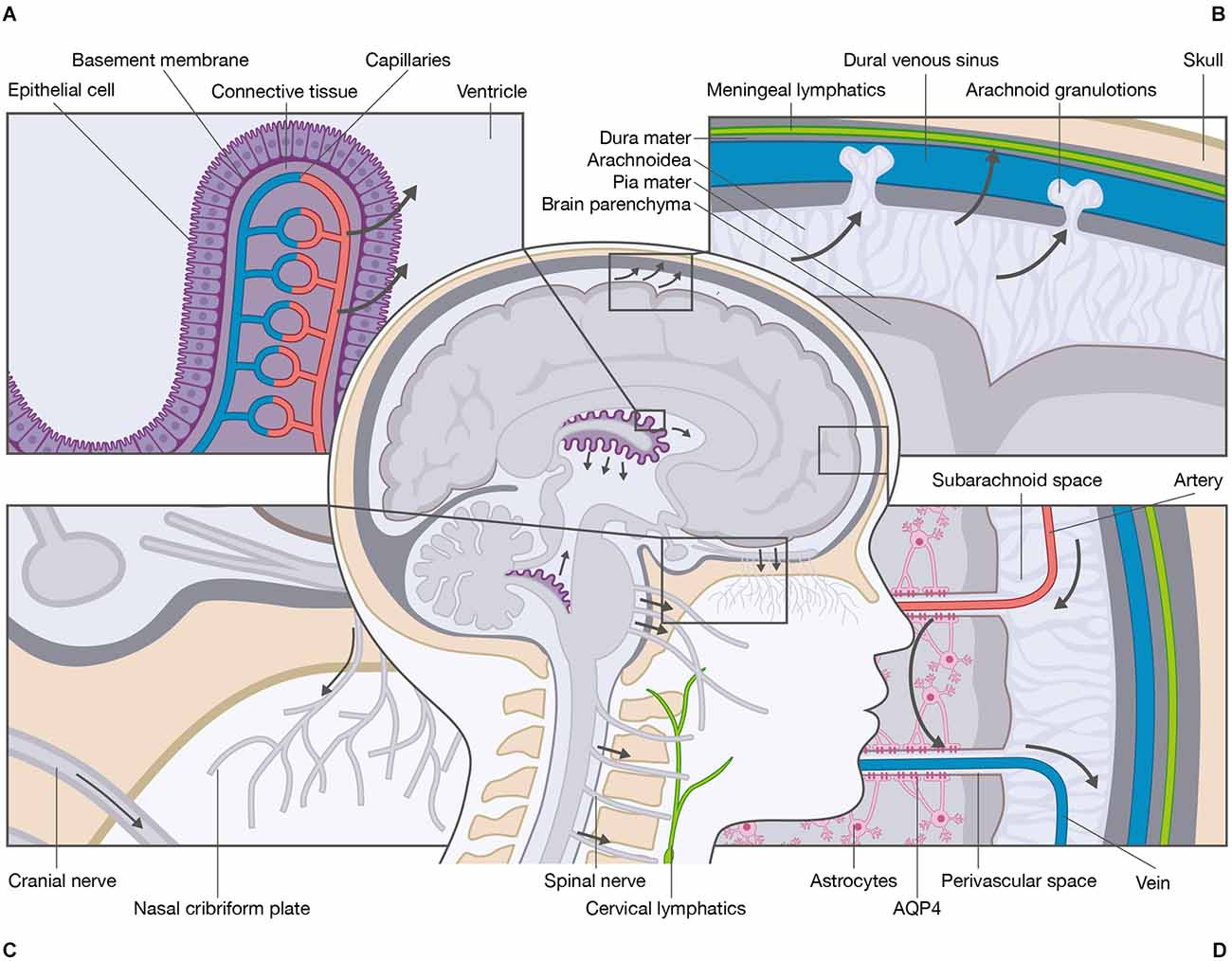

The brain and spinal cord float in a clear liquid known as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This fluid helps to protect, nourish, and remove waste from the vital tissue. Thought as the medium for consciousness, the state of the CSF will determine that of the entire organism.

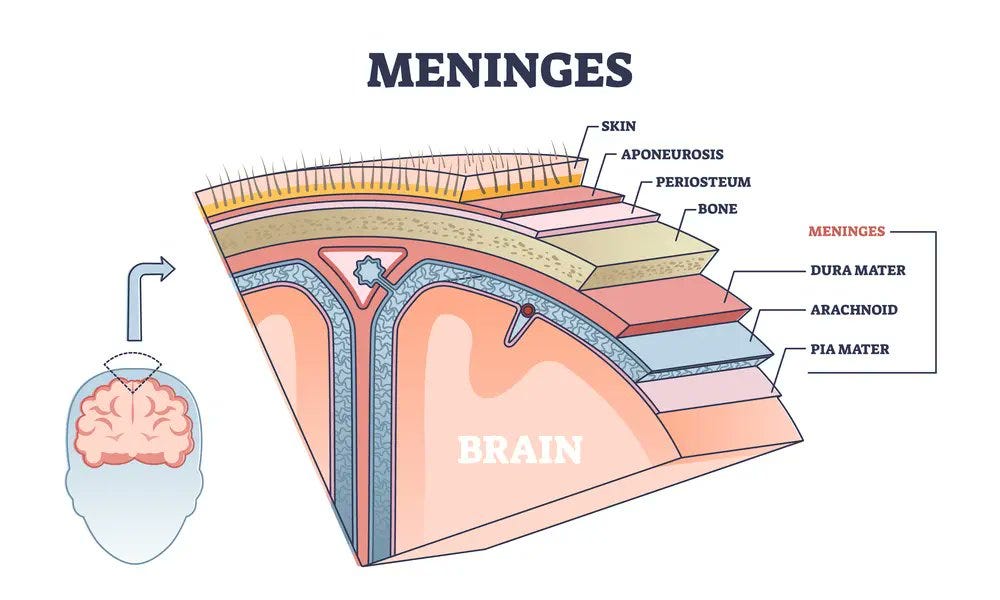

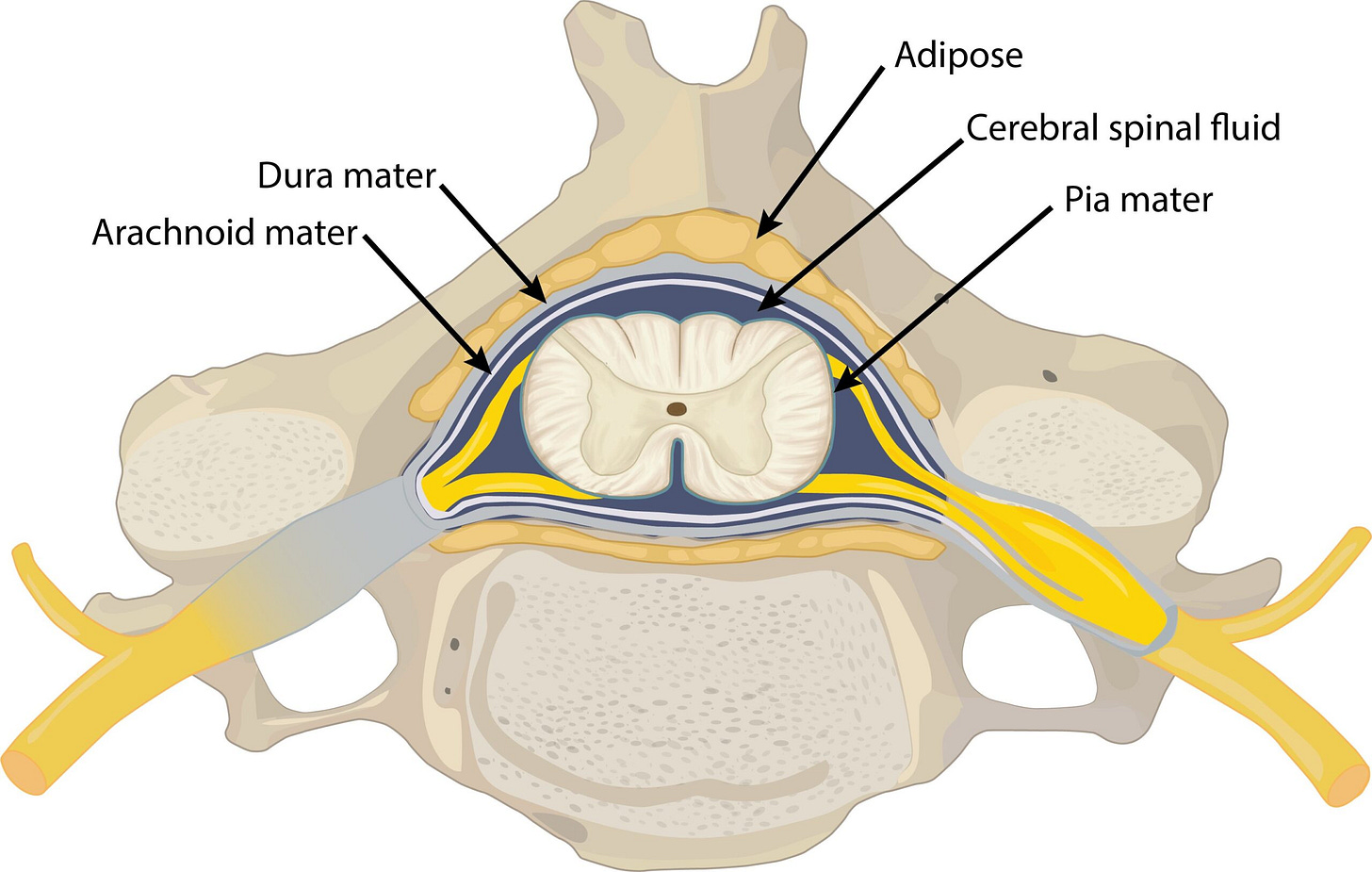

Cerebrospinal fluid is encased within the meninges, a multi-layered fascial wrapping of the brain and spine. The meninges themselves are made from strong, yet flexible collagen fibrils, and form a protective layer around the precious tissues. The outermost layer of the meninges, the dura mater, attaches directly to bones of the cranium and spine.

One of the challenges of the brain is its own weight, which would crush blood vessels within it. To work around this, the brain instead floats in a bath of CSF, providing neutral buoyancy by reducing its net weight by up to 60 times. This also serves as a cushion against physical trauma.

Made from blood plasma, CSF transports nutrients such as O2, CO2, glucose, minerals, vitamins, steroid hormones, as well as neurohormones such as dopamine and melatonin. CSF also removes metabolic waste that can damage nerve tissue if allowed to accumulate for too long. CSF functions as a complementary system to blood and lymph, as they all work together in order to ensure that the brain is well nourished and free from potential hazards.

CSF may also propagate light, allowing endogenously produced biophotons to pass through the liquid with ease. Combined with the actions of the central nervous system --as well as blood and lymph-- this supports a further centralized information and nutrient transport pathway. For living organisms, this structure is essential in coordinating and communicating the state of the internal and external world, allowing for accurate and timely adaptations.

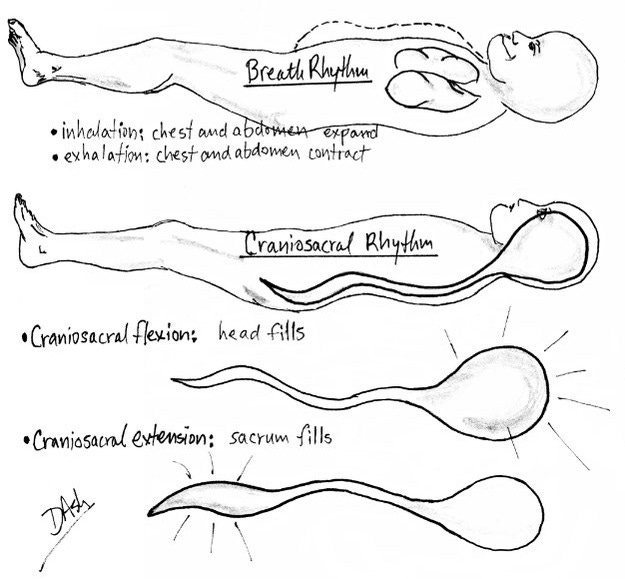

As with other bodily fluids, CSF must move to facilitate diffusion/transport. Stagnation, or limits to motion, will reduce the rate at which cells can take in nutrients and dispose of waste. This movement is known as craniosacral rhythm and is dictated by the cyclic actions of the cranium and sacrum. Any interruptions to this rhythm will cause CSF to stagnate and the central nervous system to suffer as a result.

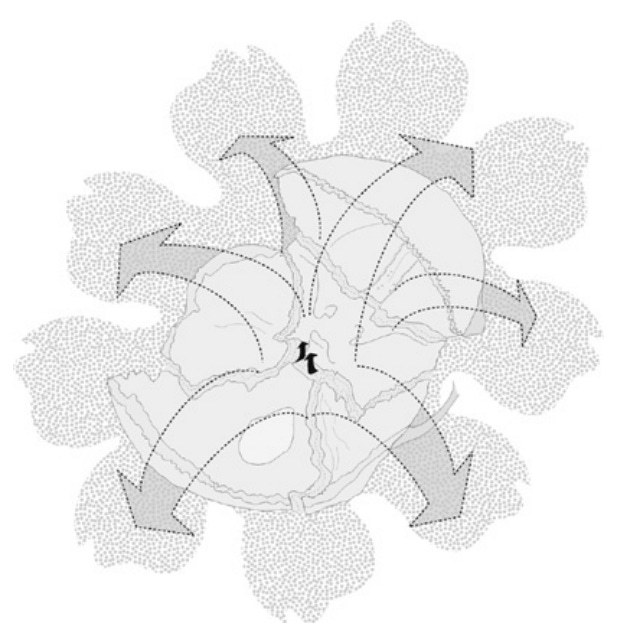

Craniosacral rhythm is predominantly synchronized with the breath, as this is an ever-present feature of life. Upon inhale, the bones of the skull splay open like a blossoming flower, expanding the meninges slightly and drawing CSF into the brain. During exhale, the skull relaxes and flushes CSF out into the spine. The sacrum mirrors these movements with flexion and extension in order to ensure maximum flow.

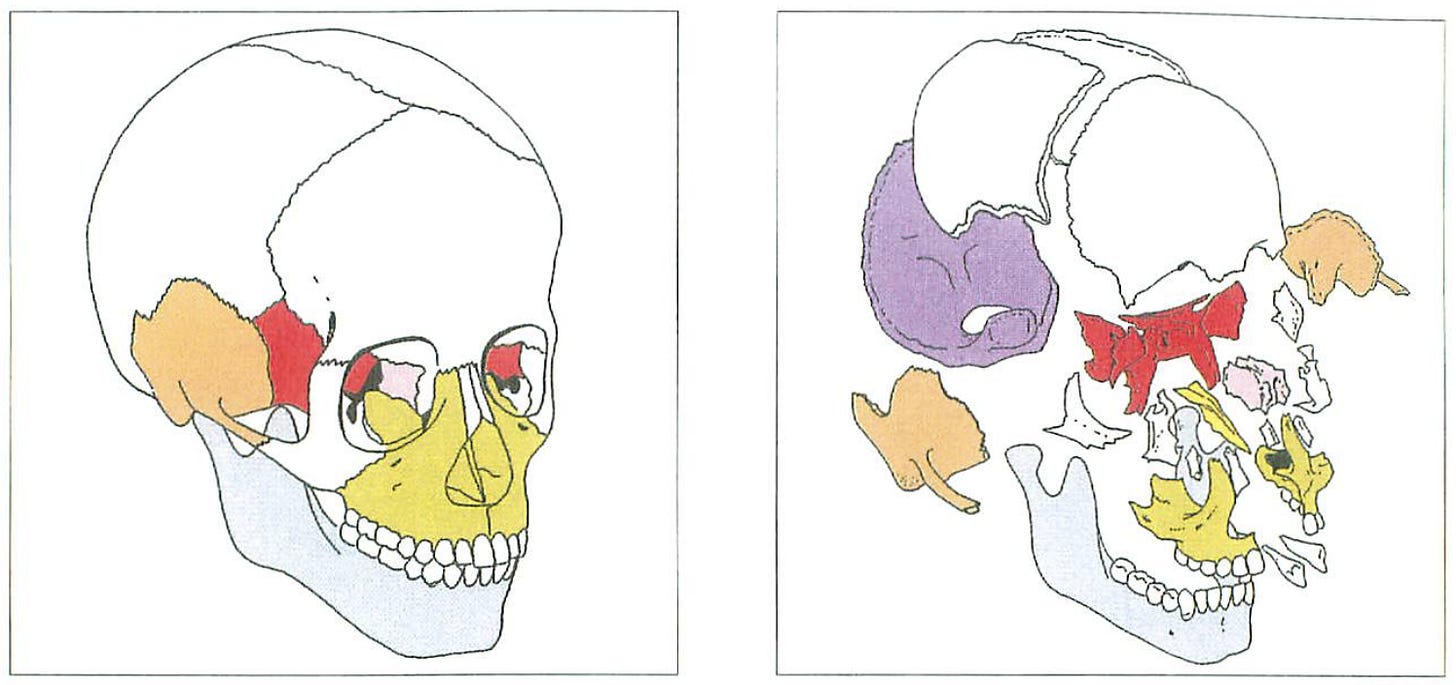

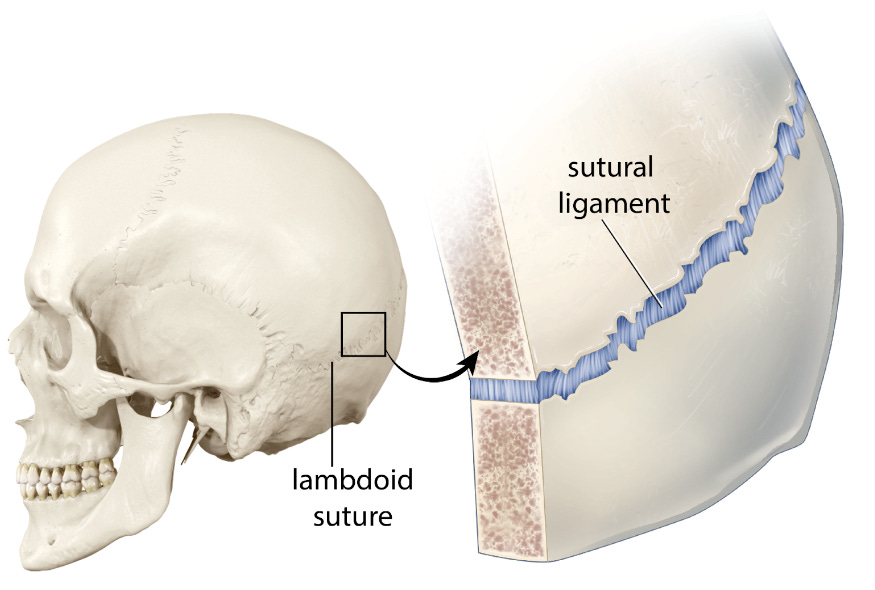

This can be difficult to conceptualize at first as the common idea of the skull is but a single, unmoving structure. In reality, the bones of the skull are a dynamic 3D puzzle of bones that articulate with one another. Motion is permitted by flexible ligamentous sutures at the joints that also maintain structural integrity. They are able to expand and contract gently in order to protect the brain while also helping to pump CSF.

The laxity of these sutures is determined by the metabolic capacity of the organism. Stress and a lack of sufficient metabolism causes these sutures, and another connective tissue, to stiffen and become resistant to movement. This is characteristic of all fascia in the body as it becomes fibrotic when energy runs dry. If this occurs at the meninges, then the diastolic reflex that further accelerates CSF during the pumping cycle will be affected.

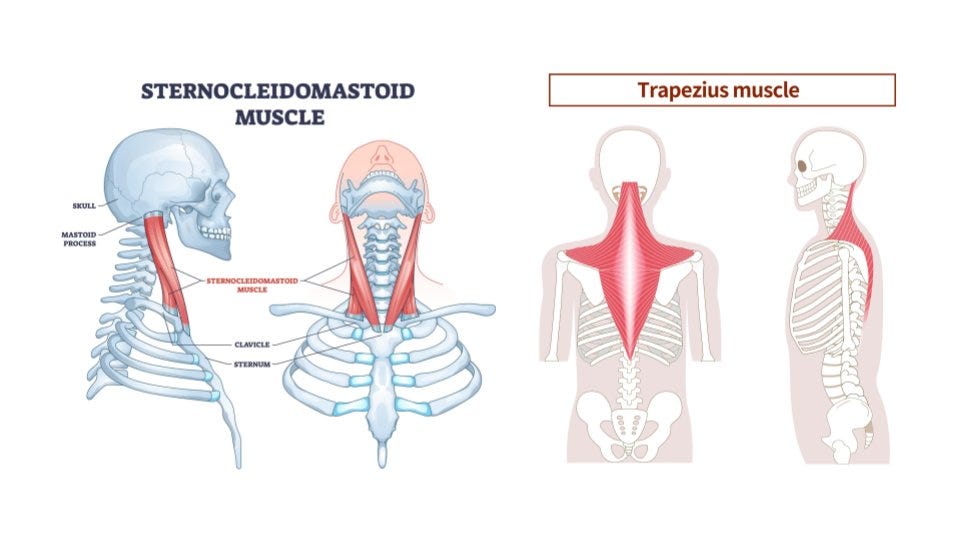

The movement is generated by the parasympathetically innervated muscles of the throat, tongue, and neck. These contract during the inhale, aiding in the expansion of both the airways and cranium. The throat and tongue pull on the sphenoid bone, while the SCM and trapezius work on the temporal bones and the occiput.

The breathing rhythm is not the only time when CSF is mobilized. This occurs any time the spine moves, such as during gait. The flexion, bending, and rotation of the spine that occur during simple movements like walking helps move fluid through the spine and brain. Since breathing is implied, the two mechanisms support one another.

Because this all happens without you needing to think, sound parasympathetic tone is then a requirement for the entire process. Stress --whether chronic or acute-- can impair the craniosacral pump through the disruption of these muscles' cyclic contraction and relaxation. Short term stress is not necessarily an issue as the individual will return to this relaxed state. However, if they are unable to relax and instead constantly stimulated, then the pump may also be inhibited.

This is a two-way street as the meninges are innervated by a number of parasympathetic nerves including the vagus, hypoglossal, facial, and trigeminal. These nerves all perceive stress to the meninges and can impact how they function. Digestion, hearing, breathing, sensations in the face, and more can all be affected by the state of the meninges. This is why, in many cases, headaches --sometimes the result of dural stretching-- are often accompanied by other symptoms.

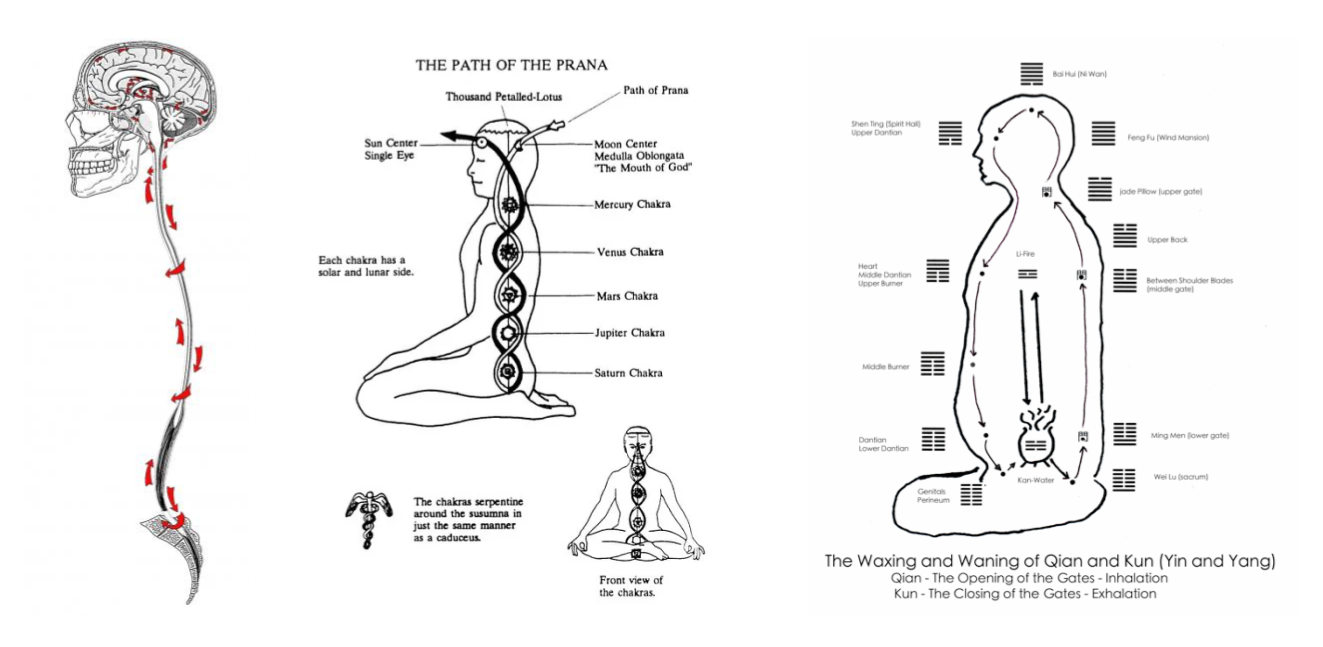

The idea of craniosacral rhythm has been known to humanity for millennia. The concept of chakras and kundalini is (likely) in reference to the flow of CSF, as blocked chakras are the result of impaired flow in the spine. The “Eye of Horus” from ancient Egypt even resembles the ventricles of the brain. This shows that while there may not have been a full anatomical understanding of CSF and the meninges, their perceptive effects upon the human being were understood and appreciated.

Craniosacral rhythm should be ever-present, running in the background, however, numerous factors may inhibit it:

Autonomic dysfunction/dysautonomia

Any form of environmental stress (chemical, physical, emotional)

Irritation of the gut (via autonomic connections)

Insufficient metabolism (sparking sympathetic/adrenal energy pathways)

Postural dysfunction (suppressing parasympathetic/irritating sympathetic nerves)

Improper breathing habits (recruiting the wrong muscles/breathing too quickly)

Injuries to the skull/spine (suppressing parasympathetic/irritating sympathetic nerves)

Avoiding/eliminating these, where possible, will allow CSF to flow as intended.

Means to improve craniosacral rhythm:

Gill breathing (breathing with your neck muscles)

Lateral eye movement

Vagal stimulation

Inclined bed therapy (helps to drain CSF from the brain overnight)

Spinal engine optimization (walking, skipping, crawling)

Sutural massages