Land-dwelling vertebrates are tasked with simultaneously propelling themselves while supporting against the constant force of gravity. This only became more of a challenge when humans started walking primarily on two legs --combined with the further growth of the cranium. At any given point in time, whether still or in motion, the spine and skull must work in unison.

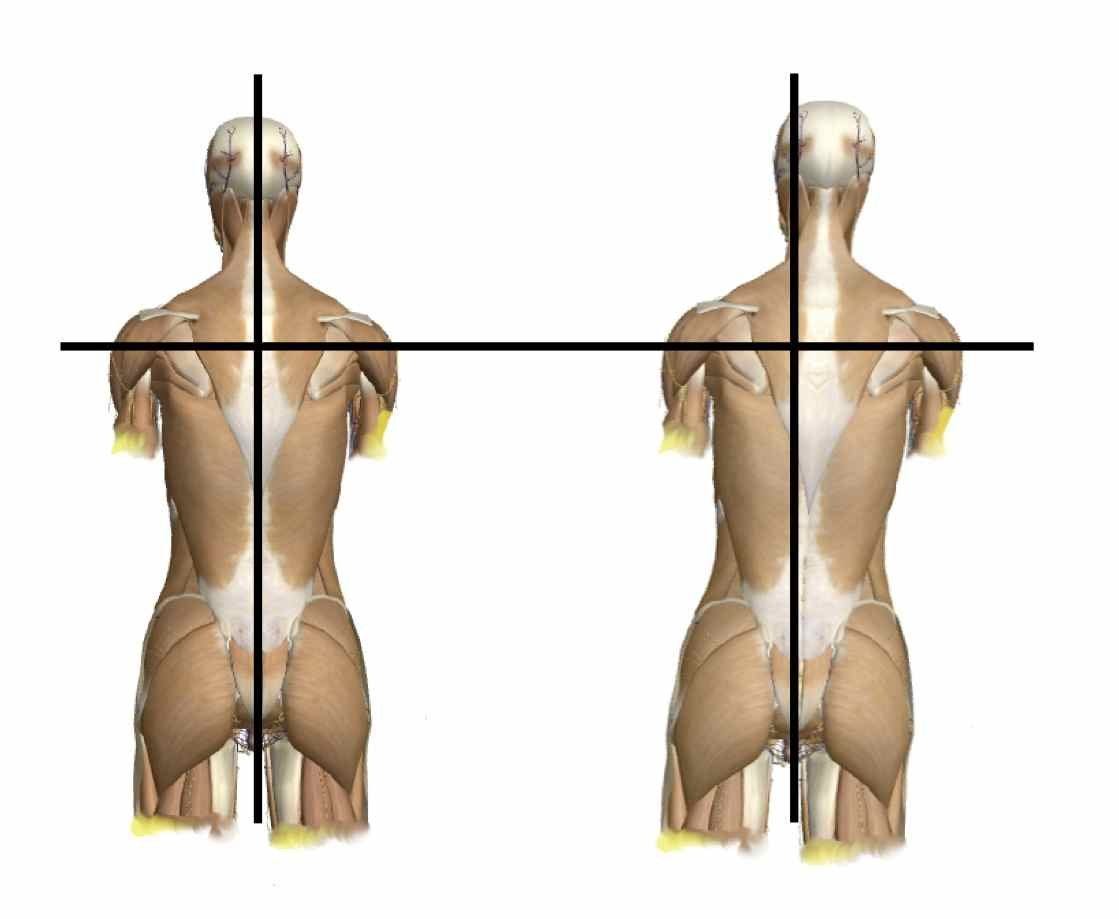

To understand why this is so important, please give my article on the spinal engine a read. The cyclic flexion and rotation of the spine is what drives locomotion in vertebrates. All the while, the head (and eyes) must remain balanced and focused forward. Any disturbances to this will not only result in impairments to movement but physical distortions to the spine itself.

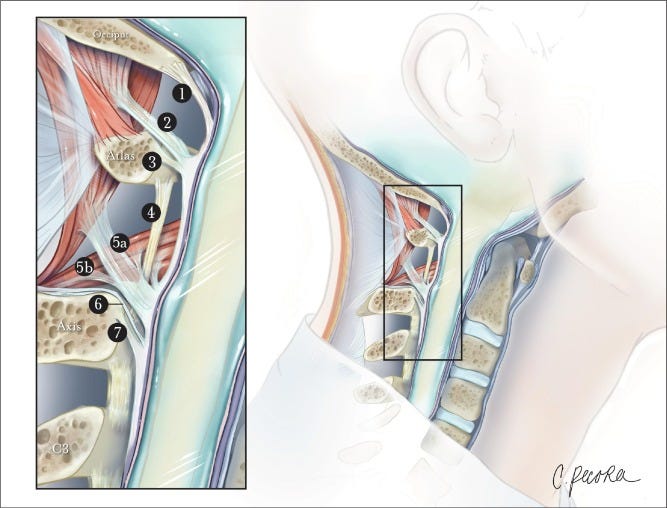

This is, in large part, regulated by the combination of the eyes and a small set of muscles that join the cranium and spine --the subocciptals. Named for their position beneath the occipital bone, these muscles function more as sensory organs due to the concentration of spindle cells within them. These cells sense changes in muscle tone/position and relay the information to the rest of the body.

You can feel this connection for yourself. With your eyes closed, place your hands on the back of your skull near the spine and shift your gaze from one side to another. You will feel the suboccipitals contract ever so gently as you do so. Due to the density of sensory cells, these muscles “feel” bigger in your holographic mental map than much larger muscles like your glutes.

While indeed small, these suboccipitals are the head of the proprioceptive chain and dictate the tone of the other, subconsciously controlled, paraspinal muscles. Visual shifts to one side will inevitably cause the entire spine to compensate (flex, rotate) subconsciously. Cats utilize the same mechanism to allow them to always land on their feet. Note how the head, neck, and eyes are among the first to move.

This is a sensory phenomenon that sits atop the hierarchy for posture and position in space. Every other part of the body runs downstream of and responds to the information from the eyes and suboccipitals. Dually because the skull/brain is essentially the command center while also being of significant mass. Thus, its position must be known and adjusted to at all points in time. Wherever the skull is, the rest of the spine must follow.

Normally, the eyes and suboccipitals coordinate rhythmically with each step, allowing the spine to flex and twist beneath. Injuries and/or bad habits can disrupt this cycle and skew the information that is being interpreted. This doesn’t mean the information is “wrong” but that it doesn’t necessarily match what’s going on with the entire body.

Eventually, this will be reflected by changes in the shape and movement of the spine. Should the eyes, or head, be shifted off to one direction the rest of the spine will adjust. Again this could be from chronically shifted gaze (eye posture) and/or injuries to the upper cervical region (whiplash).

The suboccipitals are also directly bound to the spinal cord via myodural bridges. This again means that the tone of the muscles will be sensed by the rest of the spine, and vice versa. The connection also serves as a means to regulate the flow of cerebrospinal fluid into the brain. Thus, the suboccipitals are key contributors of the craniosacral pump.

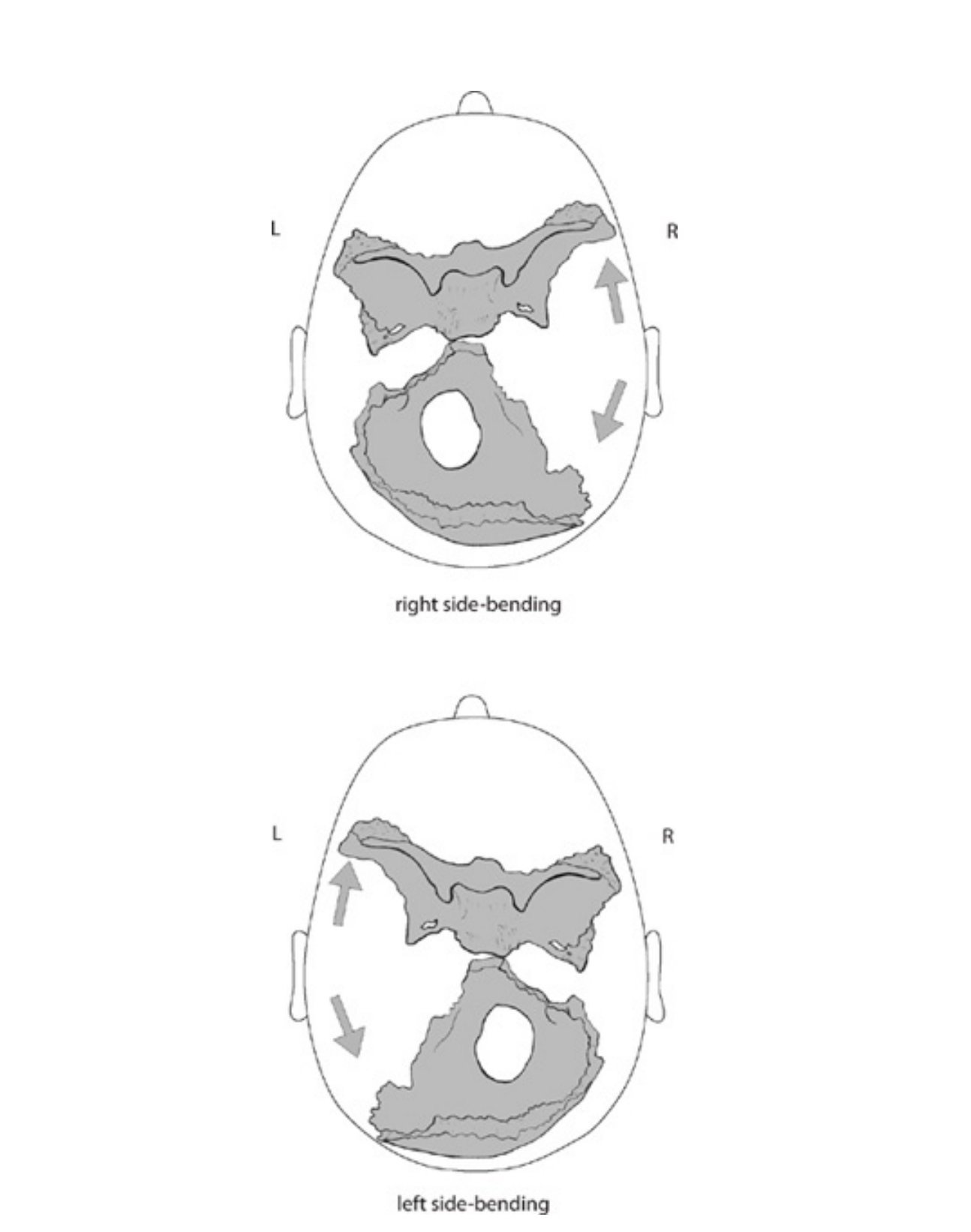

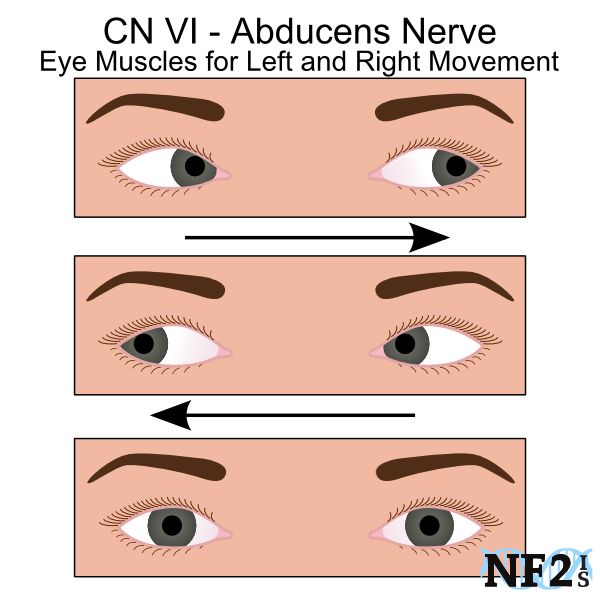

The extrinsic muscles of the eye, mainly the lateral rectus, attach to the sphenoid bone. Contraction of these muscles as the eye moves laterally then places a small amount of force on the sphenoid. This can be significant as the bone also articulates with the occiput. Chronic shifts in eye posture may alter the movement of the craniofacial complex, though this is speculative.

The easiest way to train these muscles is through lateral eye movement, simply moving your eyes from left to right in a slow and controlled manner. This can be done in two ways:

Keeping the head still and moving eyes.

Turning the head while focusing the eye in front of you.

Another exercise is to draw circles with your nose, alternating in each direction. While doing this, you may have to keep the rest of your neck still as the movement should primarily come from the upper cervical region. The slower and more controlled the movement, the better.

While doing these exercises you may yawn, swallow, or cough. This is positive feedback that you are performing the exercise correctly and highlights the connection to the parasympathetic nervous system. At the same time you may notice postural changes throughout your spine down all the way to the toes.

Lastly, take mental notice of your resting eye posture throughout the day. What side does your vision usually favor? Does this coincide with your dominant side and possibly any nagging injuries/muscle tightness? When possible, consciously correct this, either practicing gazing in the other direction or centering your resting posture. In time, this will help to build new patterns within your nervous system, yielding changes to your movement and posture.

Unbelievably top tier work. I’ve never encountered anything like this. Thank you!

Great stuff